Code generators usually create source files. The wurbelizer does not. It generates source code.

This sounds similar, but there is an important difference: instead of dealing with the complexity of whole files, the wurbelizer focuses on aspects within the files.

Generating files – even if the generator is able to distinguish between generated and manually written code – requires a lot of modeling and tooling before something useful can be generated. Files have properties like a name, are related to other files, contain code related to other code, must fit into a module or package scheme, have a structure and there is a lot more to take into account.

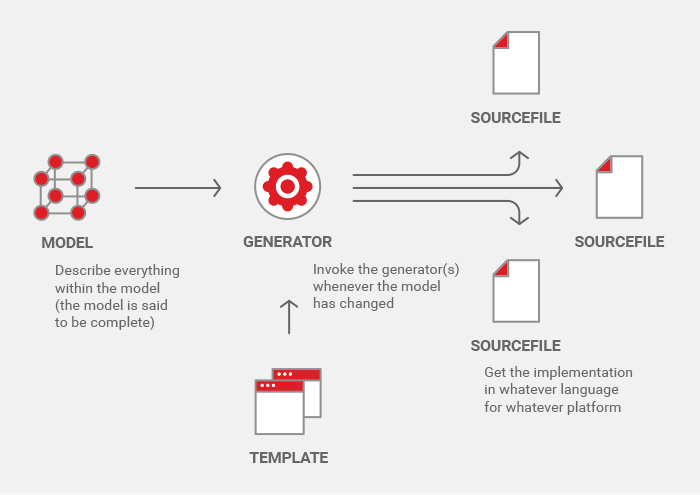

A traditional template-based approach looks like this:

The need to know so much detail before useful generators along with matching templates suited to a given model can be developed, requires hard work and stern discipline to keep the sources as a whole in sync with the model, the templates and/or the generators, respectively.

The wurbelizer, however, does not need to know anything about the overall structure of a file, how it is related to other files, its name and so on. It only needs to know how to generate some code.

The key is an inverted perspective: from the code to the model instead of the traditional view from the model to the code.

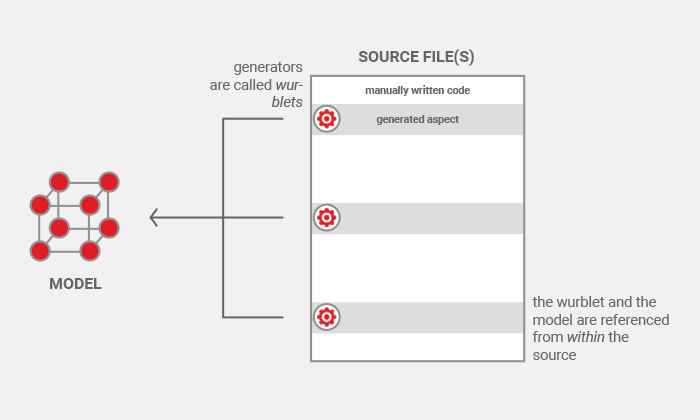

This is accomplished by embedding small generators, called wurblets in wurbelizer lingo, within the source files, like this:

The wurbelizer manages pieces of code that usually implement certain aspects. The implementation is described by the wurblets. As each wurblet covers only a single aspect, it can be kept small and simple and is easy to maintain.

Separating the How from the What

One can think of these small generators as definitions of the how, whereas the project-related modeling information describes the what. Adding generated code to an existing source file is just a matter of inserting a wurblet anchor. There is no need to add some extra stereotypes to the model and/or update the code generation process in order to make sure that other source files are not affected accidently. The wurblets, the model and the application are developed in parallel and decoupled from each other.

Living Source Code

The embedding of code generators directly within the source files leads to the illusion of a living source code. The developer explicitly declares where the code is to be generated, for which aspect and in relation to which model. This declaration is called a wurblet anchor. The generated code is completely described by the wurblet, the anchor and the model.

Wurblets are invoked by a container, the so-called wurbler. The wurbler loads the source files, scans for wurblet anchors, applies the wurblets and writes the generated code back into the source files.

Whenever the model, the wurblets or the anchors change, a single wurbelization pass — usually initiated from within an IDE — gets everything in sync by modifying the source code automatically.

Yet Another Generator Language?

Code generators need some language to describe what is to be generated. Any of these languages should provide at least features such as:

- flow-control, i.e. if-elseif-else-blocks, loop constructs (for, while, …)

- variables of different types

- operations and expressions

- functions or at least macros

- some way to access external data, especially modeling information

Usually, generators provide their own language. While this approach typically works for basic requirements, there are significant caveats when it comes to more challenging scenarios. Much effort is spent working around missing features of home-brewed languages as demands from users increase. Inevitably, the need for a full featured language arises. But why invent a new language? Couldn’t we use an existing one, like Java? Yes, we can!

This is the wurbelizer’s approach: its generator language is Java with a few and easy to learn extensions. Not only that this keeps the wurbelizer’s source code surprisingly compact, it also flattens the learning curve for the developers considerably.

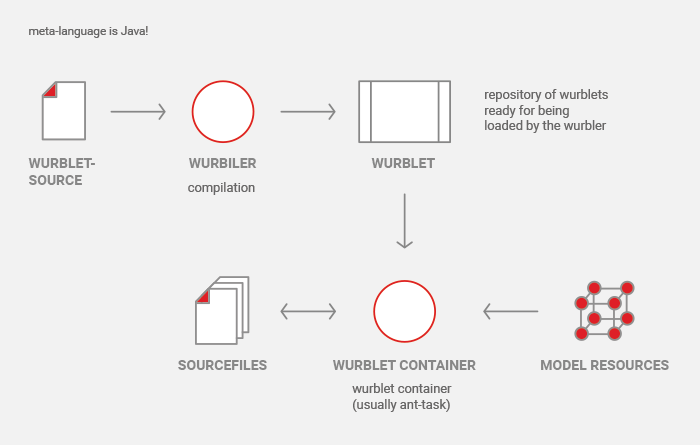

The wurblet source is compiled by a so-called wurbiler into an executable wurblet class that can be loaded and invoked by the wurbler. The wurbler and the wurbiler are usually executed from a build tool like maven.

Accessing the model

As an implication of the fact that the wurblet language is Java, the wurbelizer does not impose any restrictions or assumptions concerning the model. Accessing the model is left to the responsibility of the wurblets. Again, this keeps the wurbelizer pleasantly slim and emphasizes its claim to be a generic code generator — as generic as possible.

The Big Picture

Finally, this is how the big picture looks like:

With this approach the model, the aspects and the implementation can be developed in parallel while testable and working code can be generated even at early stages of the project. This simplifies model driven development with generative programming in agile software projects significantly.