sample. Then create a subdirectory with the name sample. In this directory create a pom.xml with the following contents:

4.0.0 com.example wurbelizer-tutorial 1.0-SNAPSHOT org.example sample 1.0-SNAPSHOT org.wurbelizer wurbelizer-maven-plugin wurbel ${project.groupId} wurblets ${project.version} com.example.wurblets

This configures the wurbelizer maven plugin to run the wurbel goal, load the wurblets from the wurblets artifact previously created and prepending the package name com.example.wurblets for simple wurblet names (non FQCN).

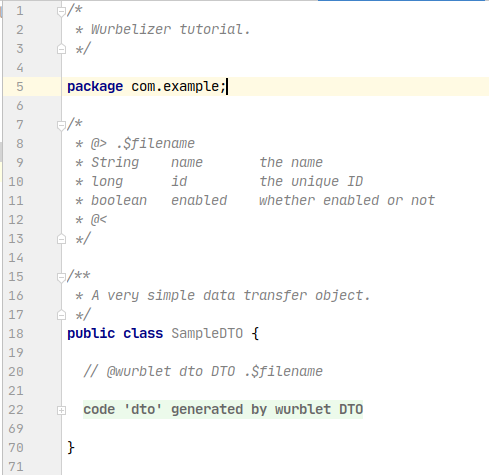

In src/main/java/com/example create a file named SampleDTO with the following contents:

package com.example;

/*

* @> .$filename

* String name the name

* long id the unique ID

* boolean enabled whether enabled or not

* @<

*/

/**

* A very simple data transfer object.

*/

public class SampleDTO {

// @wurblet dto DTO .$filename

}

The upper comment block is a here-document that describes the model. The model is stored in memory with the same name as the Java file.

The second single-line comment is a wurblet anchor. It tells the wurbelizer to create a code region (guarded block in wurbelizer lingo) named dto using the wurblet DTO created in the previous chapter.

Run mvn clean install.

That’s it! Take a look at the file in your IDE and see what happened:

The green line tells you that this is a collapsed code block that contains code generated by the DTO wurblet. Expand the block and see what’s inside. But in fact, you don’t need to because you know the model and you know the wurblet’s purpose. The code inside the block cannot contain any non-generated modifications because manual changes would be overwritten with the next build. That’s the main difference to traditional boilerplate code generated by IDEs.

Remember: the ratio of time spent reading versus writing code is well over 10 to 1!